Content taken and revised from my 2003 PhD Dissertation -> Dissertation_Mark_Nispel_2003

In the earlier post and paper, “‘Away with the Atheists’: Anti-Christian Rhetorica In Pre-Christendom” I presented an initial model of Christianity as a minority population within the Jewish community, which itself was a minority population within the Roman empire. To get a sense of the minority position of the Christian population as a setting for further topics, I will examine here the rough estimates of pagan, Jewish, and Christian populations in the Roman Empire, especially in the East.

Jewish Population in the Empire from 1 C.E. – 300 C.E.

By the first century, Judaism had spread throughout the empire. In terms of numbers, scholars have generally upheld Philo’s statement that the Jews were too numerous for Palestine to support.[1] But estimating populations in antiquity is notoriously difficult and imprecise. Feldman, in reviewing scholarly opinion, reports that scholars have estimated that there were on the order of 1 million Jews in the Land of Israel itself[2] and between 4 and 8 million Jews in the empire as a whole in the middle of the first century C.E. When this is compared to an estimated population of the entire empire on the scale of 25 – 50 million people, it is seen that Jews made up a surprisingly large 5% – 10% of the Roman population. It is thus not hard to agree with Tcherichover’s claim:

that the Jewish population was quite considerable in the Graeco-Roman world, especially in the eastern half of the Mediterranean. Greeks and Jews met at every turn, especially in the large cities, but also on the countryside, in the camps of the armed forces, in the small provincial towns, and elsewhere.

These figures indicate that the Jews rapidly grew in population from the end of the first temple period to the first century C.E. in spite of the regular social and political instabilities of their homeland.[4] It is likely that the overall Jewish population decreased somewhat in the period from 66 – 135 C.E. due to the three major uprisings that occurred.[5] Nevertheless, even if the Jewish population decreased somewhat, even drastically in some regions around Jerusalem and Alexandria, it has little effect upon the overall discussion here.

Christian Population in the Empire from 1 C.E. – 300 C.E.

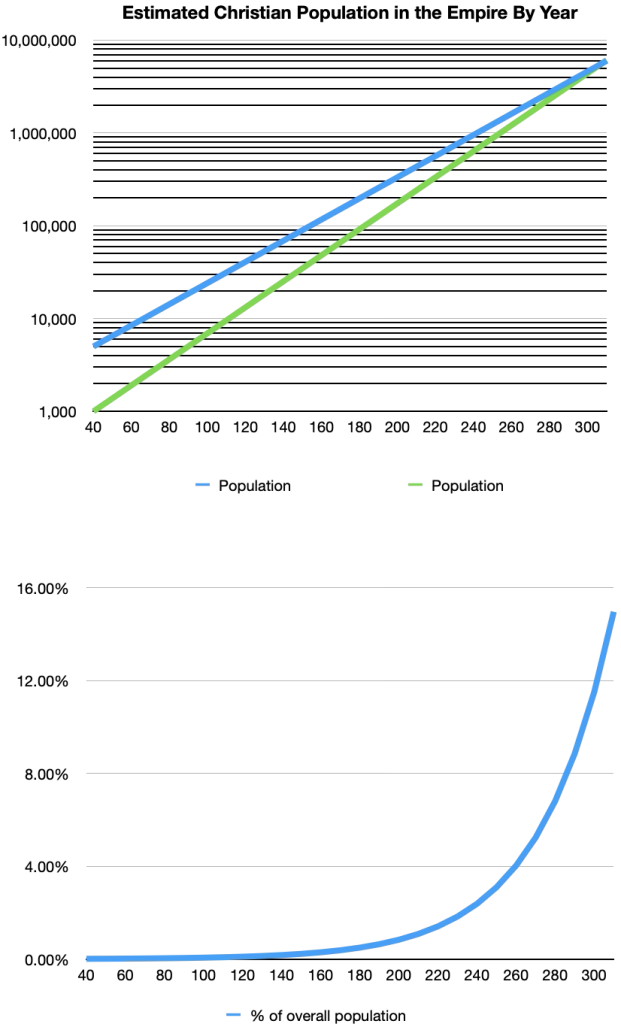

Keith Hopkins has compared these Jewish population figures with estimated Christian population figures. Scholars, such as Harnack, working with the meager data at hand have estimated that the Christian population of the empire was a maximum of 6 million at the start of Constantine’s reign in the 4th century. Hopkins then begins with another estimate that in the year 40 C.E. there were approximately 1000 Christians.[6] If we take that as a lower boundary and use Luke’s number of 5000, taken from Acts 4:4 as an upper bound, we can then use a constant growth curve to estimate the Christian population in the empire between the years 40 – 310 C.E.[7] These charts are as follows:

The numbers tell us that in the year 100, there were probably between 7,000 and 25,000 Christians in the entire empire. By the year 200, the number is between 175,000 and 332,000. Thus even with the highest number of Christians taken against the lower estimate of Jewish population of 4,000,000, the numbers indicate that there could not have been much more than 0.5% as many Christians as Jews in 100 C.E. and only 4.3% to 8.3% in 200. This clearly indicates that during the second century, Jews far outnumbered Christians in the empire, and that Christians were a completely insignificant proportion of the Roman population at large.

Observations

These numbers indicate that Judaism was not threatened in a numerical sense by Christianity until well into the third century. Only a very small percentage of Jews had to hear of Christianity and convert in order to account for the Christian population in the early second century. Having said this, it is quite certain that Jews only made up a small percentage of the Christian population by 150 C.E. In agreement with this, Justin Martyr, in a rare explicit comparison, claims that in the mid second-century Gentile Christians far outnumbered Jewish Christians.[8]

At that time, the total Christian population was probably only between 25,000 and 75,000. Even if we take Justin’s comments to indicate a ratio of only 5:1 of Gentile to Jewish Christians, this would place the Jewish-Christian population at only 5,000 to 15,000 Jews. Even if one were to go beyond this and say that the Jewish-Christian population reached 25,000 at some point, a majority of these must have been in the geographic region from Jerusalem to Antioch. This leaves very few Jewish-Christians to be spread out in Asia Minor, Italy, and Alexandria.[9]

Nevertheless, it is quite likely that the Christian movement had an impact upon Judaism beyond its sheer numbers. This is likely because the Christian movement was very active already in the first century in important centers such as Jerusalem and Rome. In addition, we know that there were Christian groups active in many of the main urban areas of Asia Minor. Paul’s letters and Acts indicate that the arrival of Christians into a city often caused a disturbance in the local Jewish population. Christians, even if not very numerous, were probably a loud and potentially annoying minority in many of these places, which required at least some response by Jewish leaders.

======================

- See Philo, Flacc 45. Similar statements can be found attributed to Strabo referring to the period of 85 B.C.E. (cited in Josephus Ant. 14.115). Also Josephus J.W. 2.398, 7.43. See Tcherikover 269-295 for a discussion of the development of the Diaspora population in various regions.

- See Feldman, 23. He cites estimates from Harnack, Juster, and Baron, varying from 700,000 to 5,000,000. Tcherichover (292-294) refers to scholars who have made use of the Jewish population in that region at the time of the British mandate in the 20th c. in order to estimate that the Jewish population in the first century C.E. was as low as 500,000 people. I have chosen 1M as a round number representing scale rather than precision, in general indicating a preference for the smaller rather than larger numbers.

- Feldman, 293. Estimates are cited from Baron (8 million) and Harnack (4 million). Josephus claims that there were 2.7 million Jews in Jerusalem who partook of the Passover lamb in 66 C.E. when the Roman war began J.W. (6.425). Philo (Flacc. 43) estimates there were a million Jewish men in Egypt. But this must be an exaggeration. Josephus states that the entire population of Egypt was only 7.5 million (J.W. 2.385). See Feldman, 555, n.20 for further discussion. He cites there a statement made by a 13th century Christian writer, Bar-Hebraeus, that a census taken by the Emperor Claudius reported a number of 6,944,000 Jews in the empire.

- Scholars have noted that the known Jewish population at the end of the first temple period must have been less than 200,000 people, isolated in the Land of Israel. This raises a serious question as to how the Jewish population grew so rapidly in the following five centuries. Scholars have proposed a variety of solutions (e.g. see Tcherichover, 293 for a discussion of various theories). Feldman uses this increase in population as an argument to support his thesis that the Jews were effective at proselytizing in this period and afterwards. Refer to the Introduction for a brief summary of the political and social forces at work in the Land of Israel in the Hellenistic period.

- Josephus reports that over 1 million Jews were killed during the siege of Jerusalem in the first war with Rome (J.W. 6.420). This is probably a gross exaggeration. Nevertheless, it indicates a large percentage of Jews living in the Land of Israel at the time.

- Hopkins, Keith. “Christian Number and Its Implications.” JECS 6.2 (1998), 192. Also see Rodney Stark, The Rise of Christianity: A Sociologist Reconsiders History (San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1997).

- This assumes the empire’s population remained constant, which scholars are pretty sure is incorrect. But there is no use trying to be too precise in this matter. The numbers must remain guidelines only. It is the magnitude of the numbers that is important here.

- 1 Apol. 53.

- This must account for why so early in the second century the patristic material only knows a Jew versus Christian dialectic and takes so little account of Jewish-Christians, who observe the law. (See Justin, Dial. 47 as an exception. Justin did know of Christians who observed the law although they did not require other Christians to do so.) These types of numbers also largely account for why there is so little explicit Jewish-Christian material which survives. Ultimately, the impact of Christianity upon the population of Judaism was exceedingly small for a very long time. Likewise, the internal influence of Jewish Christians upon Gentile Christianity became small very quickly. But the influence of the initial Jewish-Christians, especially the congregation of Jerusalem, far outweighs their actual population through their role in the transmission of the Christian exegetical traditions of the Hebrew Scriptures.

======================

Bibliography

Tcherikover, Victor. Hellenistic Civilization and the Jews. Philadelphia: Hendrickson Publishing, 1959.